Has the Economy Outgrown the Planet?

This brief introduces degrowth – intentional downscaling of the global economy to achieve ecological sustainability and social justice – for people working in environmental and social advocacy. It centers the question: “Has the economy outgrown the planet?” because global ecological limits have reshaped the conditions under which we pursue climate action, environmental justice, and many other pressing aims.

Efforts to reduce environmental harm and improve wellbeing are worthwhile on their own, even without thinking about the broader economy. At the same time, any effort to extend localized progress to planetary scale must account for ecological limits to economic growth.

This juncture calls for a diversity of already-motivated communities to challenge endless economic growth as an extension of their existing work, which begins with understanding that the economy has outgrown the planet. That awareness will help reshape our movements, our strategies, and our relationships with each other and the Earth, for the better.

Has the economy outgrown the planet?

The global economy is pushing past the ecological limits of Planet Earth, and climate change is not the only symptom.

According to the planetary boundaries accounting framework, other global-scale impacts have exceeded the “safe operating space for humanity,” including biodiversity loss, land-system change, freshwater use, and biogeochemical balance (Figure 1) [1]. Exceeding these ecological limits not only means we are losing irreplaceable parts of the natural world, from polar ice caps to entire species, but facing greater risk of disasters that threaten human health and life in general.

The data on planetary boundaries clearly show that global economic activities are pushing beyond the limits of our planet, even as our efforts to address environmental challenges have progressed [2]. Communities and innovators across the world are working hard on ways – technical, political, and cultural - to reduce ecological degradation. Yet, much of this hard-won progress is undermined by the never-ending drive to grow the economy.

Figure 1

What is the economy?

Every economic activity runs on ecological inputs. Natural materials are extracted and refined into products that we use to meet our needs. Energy is made available by burning fuels or by controlling renewable energy exclusively for human use. Food and clean water are the outcomes of many natural steps requiring sunlight, land, and microorganisms.

The economy is ecology.

Figure 2

We tend to measure the size of an economy in terms of Gross Domestic Product (GDP): the total monetary value of goods and services produced in a given nation or territory. With “the economy is ecology” in mind, every unit of GDP represents a demand for finite ecological resources, pushing on at least one of the planetary boundaries [3]. It’s no surprise then, that indicators of global ecological strain correlate well with the global GDP [4]. Global carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions, for example, have risen in lockstep with GDP for as long as fossil fuels have been the economy’s primary energy resource [5]. Biodiversity loss too stems from economic activity. Land use and waste products inevitably encroach on the living conditions of wildlife, squeezing their numbers to make room for increased economic activity (Figure 2) [6].

It turns out GDP is an excellent marker of ecological degradation, capturing a great variety of impacts across planetary boundaries. By extension, any effort to reduce impacts in one category while maintaining the drive for continual economic growth must push impacts into some other ecological realm, like the bulging of a squeezed balloon. Replacing conventional gasoline with biofuels, for example, represents a shift from climate change stress to land-use expansion [7]. Intensifying agriculture to reduce land-use requires increasing the concentration of phosphorous and nitrogen in soil, which affects biogeochemical flows [8]. Capturing and storing renewable energy in batteries requires finite materials, extracted from the Earth [9]. Every economic activity incurs an ecological cost somewhere along the way.

The next great challenge for environmental advocates is to recognize that a limit on ecological degradation means a limit on economic size [10].

Why can’t we have sustainability and growth?

At the global level, economic activity and ecological degradation are inextricably linked, but this relationship is not always obvious at the scale of a single company or community. At the local level, there are countless opportunities to reduce negative outcomes while maintaining production and consumption; from reducing toxic ingredients to better utilizing inputs. Such activities are considered more “sustainable”, and in recent decades the sustainability movement has been a gathering place for advocates and professionals to explore how we can do more with less.

In the name of sustainability, individuals have changed their lifestyles and purchasing habits, companies have committed to reducing their carbon and water footprints, engineers have developed more durable products and less wasteful manufacturing techniques, and communities have come together to cultivate urban farms, install solar power, reduce pollution, restore ecosystems, and share resources. These achievements are impressive, and they have laid a foundation for more ecological ways of thriving together. At the same time, these efforts remain situated in a global economy committed to endless growth. In this economic system, ecological resources represent economic opportunities, meaning that the savings achieved by one sustainability effort are another’s opportunity for extraction and profit. That’s exactly why, for example, global carbon emissions continue to rise, even as the carbon intensity of the economy (emissions per unit of GDP) is falling [11].

The economy is getting more efficient, but the savings are fueling further growth and extraction, not resource conservation, environmental protection, or ecological health.

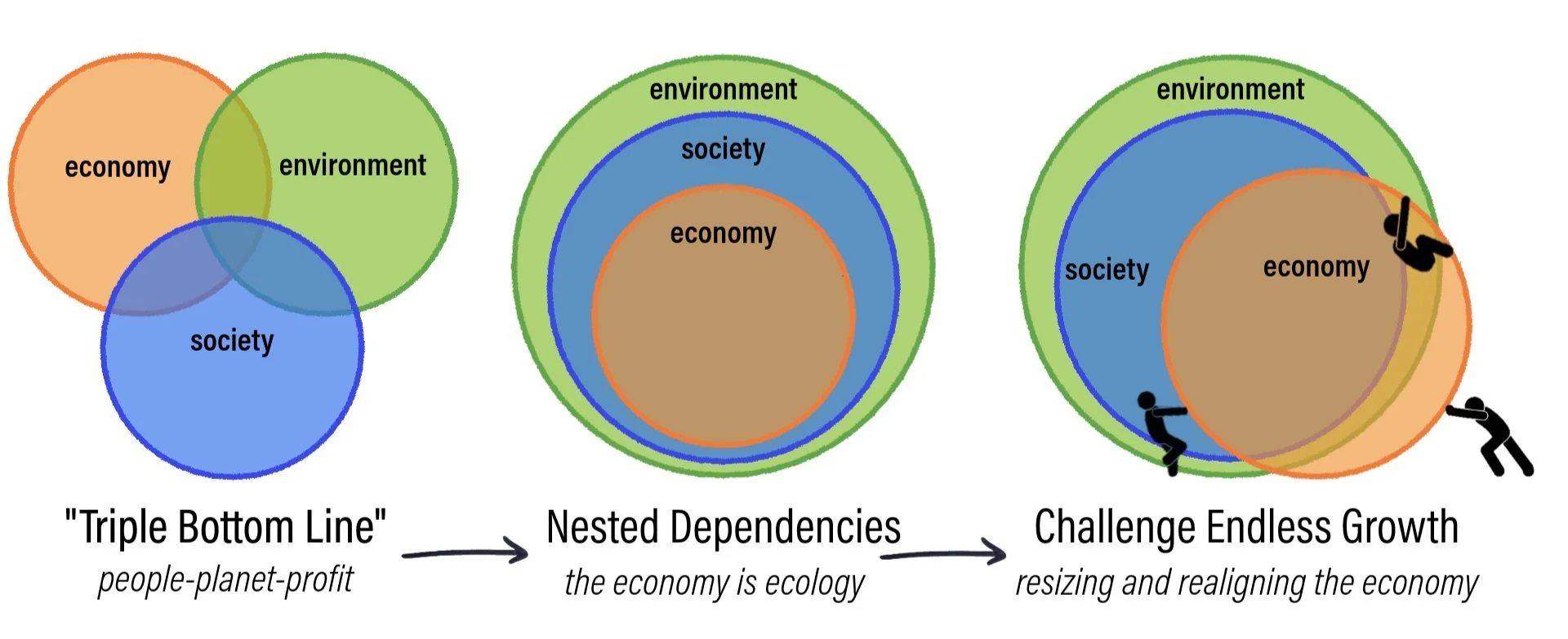

In recent decades, the common understanding of sustainability’s mission evolved away from the “triple bottom line” of people, planet, profit and toward an understanding that the economy is just one product of global society [12]. Our whole socioeconomic system arises from the ecological functioning of Planet Earth. It's time for sustainability’s next evolution (Figure 3). In this view, we recognize that a) the economy has outgrown the planet, and b) it has failed to align with social justice and ecological needs.

Figure 3

How much is enough?

This understanding of sustainability within limits will lead us to call for an end to endless growth, and a realignment of social and ecological goals.

Challenging endless economic growth does not mean calling for every aspect of the economy to be scaled back. What is needed is not economic restraint across the board, but a rebalancing of priorities. When your luggage is too heavy, you don’t leave behind one of everything you’re carrying; you find the densest things of least importance to part with. As we scale back ecologically destructive activities, we also have the exciting opportunity to revive ways of meeting our needs that responsibly steward the environment and improve human wellbeing. We know, from both long-standing tradition and from empirical data, that we can live better within limits.

Our globally-shared economy can both get smaller and still provide enough for everyone to live a healthy and dignified life, far more effectively than it does today. It’s an unprecedented challenge, but one that brings opportunities to make long-sought updates to how resources, knowledge, and power are shared across the globe. It's time for the political will behind sustainability to support the emerging global movement for economic downscaling, aimed at living better together. This is the degrowth movement.

What is degrowth?

Degrowth is an intentional downscaling of the global economy for the purpose of achieving ecological sustainability and social justice.

Degrowth is not a recession, a temporary austerity measure, or a “going backward” to “simpler times.” Instead, degrowth seeks to ensure that global society's modern needs can be met while a smaller, more just economy is sustained long into the future, combining local efforts with a global reduction in pollution, emissions and consumption [20].

Backed by a combination of traditional knowledge, planetary awareness, and lived experience with the struggle for ecological health, the desire to move beyond growth is gaining momentum. Many policies compatible with a smaller economy, such as restrictions on advertising, caps on fossil fuel use, and work-life balance incentives, are already gaining in popularity [21]. As the movement expands, we continue discovering new opportunities for optimistic collaboration under the banner of degrowth.

Sustainability buzzwords come and go, but degrowth is distinct because it adds macroeconomic context to the hard work that environmental and social justice advocates have been doing across the globe. It reminds us to continue this work in our own communities, while also moving, pushing, away from the global economic growth paradigm, and disentangling wellbeing from the perceived need for an ever-increasing GDP [22].

While many societies have achieved this locally, economic downscaling has never been tackled on a global scale.

The word “degrowth” may be uncomfortable because the task is daunting, if not inconceivable. How will we ever stimulate the social and political will to pursue economic downscaling, or even speak to friends, family, and collaborators about such a desire? How can we trust that such a path will be followed with fairness and justice? Thinking in terms of degrowth and collective wellbeing is a paradigm shift. It requires unlearning the assumptions and priorities of a growth economy, acknowledging the complex connections among global society, unveiling impacts – both intended and unintended - and learning to live better within limits [23,24].

Who is degrowth for?

Figure 4

Reducing economic activity is for some. Degrowth is for all.

Degrowth entails a right-sizing of wealthy economies, bringing our outsized ecological demands in sync with what Earth can sustain, known as a “One Planet” ecological footprint [25]. At current production and consumption levels, the global economy would need 1.7 Planet Earths to be sustained without further disrupting planetary boundaries. Furthermore, only a small portion of society is responsible for this overreach, given the concentration of economic power in the hands of a few. Degrowth aims at a fair-share allocation of resource consumption, all within a smaller economy. This means economic downscaling for the wealthy, but also economic opportunity for many more. We’ll need growth in some industries - especially ecological restoration, alternative energy, and active transportation – and contraction in others.

Ultimately, degrowth is a multilateral movement, including many aspects of environmental, economic and social justice action, with strategies tailored to different contexts. [25] We’ll need people from all walks of life to contribute to the vision of a thriving global economy that is smaller and in tune with ecological needs, grounding our economies in reciprocity with the planet.

That’s why stimulating the challenge to endless growth is central to Degrowth Institute’s mission.

Where do we go from here?

Recognizing that the economy has outgrown the planet elicits a conflict. The assurance that biophysical limits to growth can be articulated and addressed is countered by an overwhelming sense that the path to economic downscaling will be impossible to navigate. How do we start building a just and ecological future when the cultural values and political practices required seem so distant from the current norm [27]?

Facing such formidable questions is the work of social movements. From this point of inflection, we will need to work together, not simply on the action of economic downscaling, but on creating a shared understanding of what it means to live life well, together, and within planetary limits. As we build the degrowth movement in the United States, there is a wealth of wisdom and ongoing action to be drawn upon (Figure 5).

Figure 5

If you want to join the challenge, here are some actions you can take:

Read Up

Check out our Toolkit, where we’ve compiled a short list of suggested readings on degrowth and movement-building, from social and environmental leaders such as Octavia Butler [28], Martin Luther King Jr. [29], Robin Wall Kimmerer [30], and Daniel Quinn [31].

Peruse our Research, which connects sustainability, circular economy, social justice, and the energy transition with the need to challenge endless economic growth.

Take Action

Spark an ongoing dialogue by setting up a Degrowth Cafe in your community.

Stimulate a conversation at your company, organization, or college/university by hosting a Campus Dialogue.

Connect

Contact us at info@degrowthinstitute.org

References

[1] Richardson, K. et al. Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries. Sci. Adv. 9, eadh2458 (2023).

[2] Potsdam Institute. Planetary Boundaries – defining a safe operating space for humanity. Postdam Institute for Climate Impact Research https://www.pik-potsdam.de/en/output/infodesk/planetary-boundaries/ (2024).

[3] Czech, B. The trophic theory of money: Principles, corollaries, and policy implications. J. Proc. R. Soc. New South Wales 152, 66–81 (2020).

[4] World Bank. GDP, PPP (current international $). World Bank Open Data https://data.worldbank.org (2025).

[5] Global Carbon Project. GCB 2025. Global Carbon Budget https://globalcarbonbudget.org (2024).

[6] WWF. Living Planet Report 2024 - A System in Peril. https://wwflpr.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/2024-living-planet-report-a-system-in-peril.pdf (2024).

[7] Lark, T. J. et al. Environmental outcomes of the US Renewable Fuel Standard. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119, e2101084119 (2022).

[8] Steffen, W. et al. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 347, 1259855 (2015).

[9] Riofrancos, T. et al. Achieving Zero Emissions with More Mobility and Less Mining. Climate and Community Institute https://climateandcommunity.org/research/more-mobility-less-mining/ (2023).

[10] Mulrow, J. Sustainability’s Next Great Challenge: Moving Beyond Growth. Habitable https://habitablefuture.org/resources/sustainabilitys-next-great-challenge-moving-beyond-growth/ (2025).

[11] Global Carbon Project & Maddison Project Database. Carbon intensity: CO₂ emissions per dollar of GDP. Our World in Data https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/co2-intensity?tab=chart&time=1990..latest&country=~OWID_WRL (2024).

[12] Elkington, J. 25 Years Ago I Coined the Phrase “Triple Bottom Line.” Here’s Why It’s Time to Rethink It. Harvard Business Review (2018).

[13] Abazeri, M., Mulrow, J., Pai, S. & Ajl, M. A Degrowth Perspective on Environmental Violence. in Exploring Environmental Violence: Perspectives, Experience, Expression, and Engagement (eds. Fuentes, A., Lederach, J. P. & Marcantonio, R. A.) 208–222 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2024). doi:10.1017/9781009417150.012.

[14] Kimmerer, R. W. The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World. (Scribner, New York, 2024).

[15] Millward-Hopkins, J., Steinberger, J. K., Rao, N. D. & Oswald, Y. Providing decent living with minimum energy: A global scenario. Glob. Environ. Change 65, 102168 (2020).

[16] Moore, J. & Rees, W. E. Getting to One-Planet Living. in State of the World 2013: Is Sustainability Still Possible? (eds. Assadourian, E. & Prugh, T.) (Island Press, Washington, DC, 2013).

[17] Aritza, A., Kraus-Polk, J. & Luz Cordel, S. California Doughnut: A Snapshot of California’s Social and Ecological Performance. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1_7z6xzu-CNmF3dndfavaH8ykMDxp7Aq6/view?usp=drive_link&usp=embed_facebook (2024).

[18] Tyberg, J. & Jung, E. Demystifying Degrowth. https://explore.degrowth.net/degrowth/demystifying-degrowth/ (2021).

[19] Orsagh, M., Linn, A. & Rocco, S. By Disaster or Design. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/6729db674462bc7a120a6333/t/680881953599ee22d2fe7f9d/1745387965521/By-Disaster-or-Design_Arketa-Institute.pdf (2025).

[20] Bliss, S., Mulrow, J., Egler, M. & Barbieri, L. Degrowth and Sustainable Consumption. in Language for Our Common Future: A Vocabulary for Sustainable Consumption and Lifestyles (Routledge, 2025).

[21] O’Dell, D., Contu, D. & Shreedhar, G. Public support for degrowth policies and sufficiency behaviours in the United States: A discrete choice experiment. Ecol. Econ. 228, 108446 (2025).

[22] Kallis, G. et al. Post-growth: the science of wellbeing within planetary boundaries. Lancet Planet. Health 9, e62–e78 (2025).

[23] Czuprynski, Z. Unlearning Growth: Reclaiming Higher Education for Sustainability. Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy https://steadystate.org/unlearning-growth-reclaiming-higher-education-for-sustainability/ (2025).

[24] Dahmm, H. A Blind Look at Collective Blindness. resilience https://www.resilience.org/stories/2023-05-30/a-blind-look-at-collective-blindness/(2023).

[25] Assadourian, E. The Path to Degrowth in Overdeveloped Countries. in State of the World 2012: Moving Toward Sustainable Prosperity (ed. Starke, L.) 22–37 (Island Press/Center for Resource Economics, Washington, DC, 2012). doi:10.5822/978-1-61091-045-3_2.

[26] Reyes, E. What Is Degrowth? https://wedo.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/1.-What-is-Degrowth_EN.pdf (2024).

[27] Mercury, A. How Do You Begin to Heal a Wound You’ve Never Lived Without? https://annamercury.medium.com/how-do-you-begin-to-heal-a-wound-youve-never-lived-without-b2d2cbceeff6 (2024).

[28] Butler, O. E. Parable of the Sower. (Grand Central Publishing, New York, 1993).

[29] King, Jr., M. L. Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? (Beacon Press, Boston, 1968).

[30] Kimmerer, R. W. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants. (Milkweed Editions, Minneapolis, Minn, 2013).

[31] Quinn, D. Ishmael: An Adventure of the Mind and Spirit. (Bantam Books, New York, NY, 1992).

[32] Hardaway, K. et al. Has the Economy Outgrown the Planet? An Introduction to Degrowth. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/368531755_Has_the_Economy_Outgrown_the_Planet_An_Introduction_to_Degrowth (2023) doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.32074.85449.

June 2025

CC BY-SA 4.0

Degrowth Institute, Chicago, IL

Corresponding Author: John Mulrow

Editing and Design: Anna Prouty

Conceptualization: Jason Barahona Rosales, John Mulrow, and members of Degrowth Coffee Hour at Purdue University. The title is inspired by Hardaway et al. (2023) [32].